The Annual Sue Ryder lecture, delivered on March 6th at the Houses of Parliament

Good evening. First of all – thank you for the great honour of speaking on this occasion. On November 7th 2017, my wife, Fiona died at home whilst under the care of our wonderful Sue Ryder team. The meticulous expertise and deep compassion which they brought into our home are things I shall never forget. The debt I owe to them is both indescribable and unpayable – and if tonight’s words make some small scratch on its surface, I shall be pleased.

Let me make a confession: I hate writing postcards. As a child, whenever we would travel on holiday – the responsibility for doing so would be divided up between my brother and I. One would write to Granny, one to Auntie and so on. I hated it. I would write in the biggest possible script so as to minimise the number of words required – and I am sure they were as boring to read as they were to write. Years later, travelling with children of my own – the same rules applied. Fiona and I would parcel out between us who was writing to whom. Out would come the big handwriting, and my reluctant words would fill up the page and disappear into the post-box.

So why, seven days after Fiona’s death, did I find myself coming home from a walk across the crunching, frosted grass of the cemetery, to write a postcard? It was because I felt as if I were abroad. Everything looked the same, the landmarks were still in the same places, the cars still drove on the left – and yet somehow, I had been transposed into an alien place. A shift had gone on so that the familiar became unfamiliar, the reassuring became disturbing and I didn’t belong. Like shopping in a foreign supermarket – I inadvertently bought the wrong things, or the right things in the wrong quantities. Like a stranger living abroad, I found that my calendar seemed to have different dates to those marked on other people’s. My milestones were not theirs. Like a newbie on foreign soil speaking a foreign language all day – I was exhausted by teatime…or often by lunchtime.

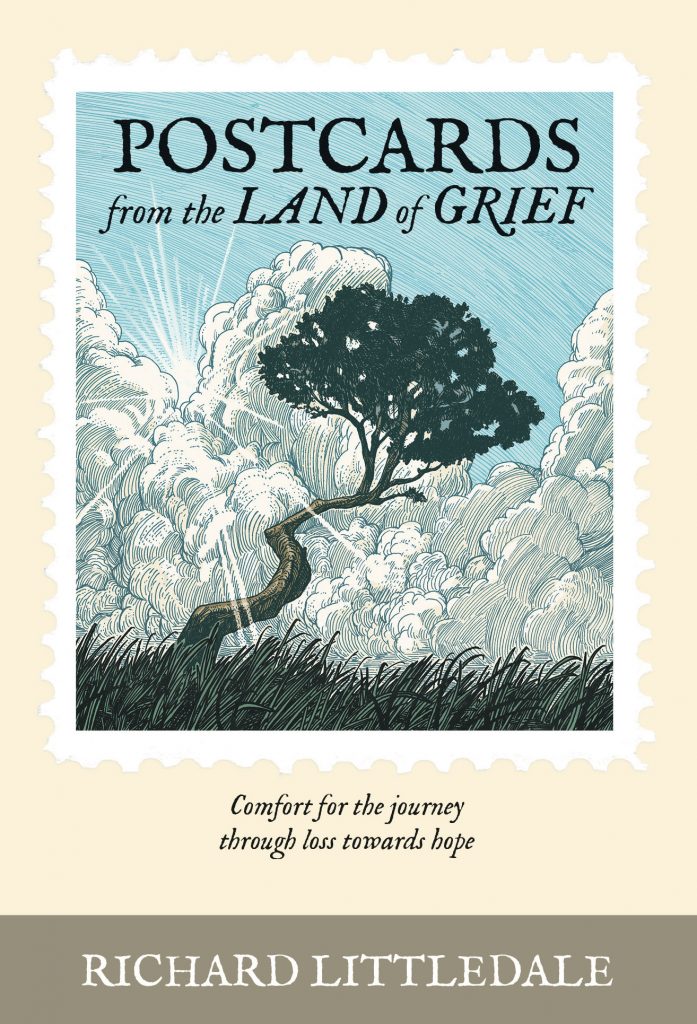

And so, I began to chart the experience through a series of some thirty ‘Postcards from the land of grief’. Initially they were published on my blog, and received lots of interest. Later they were featured on BBC Radio 4’s “Sunday worship” – provoking one of the biggest audience responses that programme has ever seen. A little later this year they will appear in a book, and there is every indication that there is a good appetite to read them. Other people live in this foreign land of grief too, it would seem. Their friends and family see them there, separated by an invisible border and o so far away. They want to help, but as we now know – 51% of them are afraid of saying the wrong thing.

So perhaps tonight I can read you a postcard or two – sent from that foreign land to all of you here tonight. This new research has shown that bereavement is a ‘very individual phenomenon’. As a minister of religion for 30 years, I am no stranger to death. I have been there at the bedside as a person slips away. I have been there just afterwards, with the body in bed and praying with family. I have been there to discuss the funeral. I have been there to conduct the funeral. I have been there to visit the family after it and see how they are doing. Despite all of that, my arrival in the land of grief was a rude shock:

A new topography

I am learning that the landscape of grief is a strangely unnerving place. In part its strangeness is that those things which you had thought would be familiar…are not familiar at all. Grief can turn a soft memory into an unforgiving rock face or a hairbrush into a sword to pierce the heart. Regrets, like injected foam, expand to fill the space you give them. Words spoken or heard are like an old cassette left next to a magnet – muffled by exposure to greater force.

To arrive in that land is to find yourself in a place which is both close to and distant from what you always regarded as normal:

Invisible borders

I once heard a refugee describe how the border with his home country ran just alongside his refugee camp. He could stand at the edge of the camp and gaze across at an old familiar tree in the home country – but he could not go there. The border was both invisible and impervious.

I am finding that the landscape of grief has just such a border. I can gaze across it at old familiar things. I can watch normal life unfold before my eyes, and I can stand and have a conversation with those across the border as if nothing separated us. That said – it is impossible to cross for now. When it comes down to it, they live there and I live here and nothing can be done about that. I make occasional forays into their land, and they are precious. It turns out, though, that I take the border with me. I am like a cartoon character racing to outrun an elastic band – legs whirring and arms pumping, but the snap of the elastic must bring me back as surely as night follows day.

The refugee made a new life for himself across the border. He would still gaze from time to time at the old, familiar tree – but he found others in his new home. Like the old one, they provided shade and the kind of mental landmark which makes any new place a little less strange. Today, I shall go looking for trees…

The report will demonstrate that ‘knowing support is on hand increases resilience’ and that has certainly been my experience. ‘Kindness’ is an old-fashioned word which seems to belong to an age of innocence, and yet it sustained me in those early days:

The currency of kindness

It continues to surprise, this land of grief. Its topography is so hard to read – like the shifting sands of the desert. To climb a tiny hill can feel like scaling a mountain – leaving the lungs gasping for air at the top. Once scaled – the view behind may be spectacular – but the view ahead is hidden, at least for now. Some of the valleys which look like no more than a ditch prove to have sides so steep that they all but blot out the light.

As ever with foreign travel, the currency is unfamiliar too. Money has little value. It can pay the bills and provide some distraction, but it has no real worth. After all, it could not pay any fee to prevent crossing the border into here. In this land the currency is kindness. It comes in words and actions, cards and letters, and even smiles.

I started this week by re-reading all the cards and letters which I have received. They came from every direction, in every kind of handwriting and from every age. Some were poetic, some fulsome, some brief – but all have made me richer here.

I thank God for every single one of them. Like money sent home from abroad – they have helped to sustain life in this foreign land and I am humbly grateful.

As many told the researchers, there is an awkwardness about seeking help. The version of ourselves which needs to reach out for it is one which we neither recognise nor welcome. To admit to loneliness is to admit to a form of social plague, it feels:

A cross-border confession

When I used to live in that other place, holidays to France were an annual feature. The rumble of the wheels down the ferry ramp and the first sight of a French flag fluttering over the port always brought a frisson of joy. So, too, did speaking another language. The sheer fact of speaking a different language and saying different things made me feel like a different person. I could say them ‘over there’…

I am about to write something from ‘over here’ which I could never have written ‘back there’. I could never have written it because it would have been embarrassing and awkward. I would never have written it because it would have been untrue. Nonetheless, I write it now. I am lonely. Married to Fiona for 30 years, and in love with her for longer than that, life without her by my side is shockingly different. One day last week a 24-hour period passed where my only conversations were on the phone or with a cashier at the supermarket. Mine is by no means a unique experience, and I have endured it for a far shorter time than many. All the same, it is a shock to find that it is true.

For those who are scrolling for the comments box even as they read this, I wanted to write a message or two. Firstly – thank you. Your kindness and warmth are a reflection of God’s image in the foxed mirror of humanity, and it is wonderful to see.

Secondly, please be assured that my loneliness is neither your problem nor your fault. You did not cause it and I do not count it as your duty to rectify it. Your attempts to distract me from it are always welcome, and the place in your heart from which they come is very dear. Please don’t be surprised, though, if I do not always accept them. The reason for my refusal has everything to do with me and nothing to do with you. Part of the collateral damage of bereavement is a wastage of the confidence muscle, if there is such a thing. That muscle which heaved body and soul up over the parapet of home has shrunk, you see. I look out over the threshold of home to a landscape filled with life, laughter, food, drink and conversation and I both move towards it and quail from it. I will learn, and the muscle will grow back, but it may take a little time.

Thirdly, please don’t let the sea-mist of sadness which sometimes rolls off me put you off from telling me about your life. I want to know. I want to hear the shrill sound of laughter and the clatter of ordinary dishes and the occasional curse! It reminds me that there is a life out there, beyond the mist – and I still belong to it.

The forthcoming report will talk about the importance of community in addressing what is essentially the individual problem of grief. I could not agree more – and I am fortunate to find myself in the midst of this painful and challenging experience with a faith community gathered around me. However, sometimes the least tolerant or understanding person within the circle surrounding the bereaved person can be …the bereaved person. I found myself too often in the company of people whom I described as Mr Shouty, Mr Angry and Mr Selfish. Between them they would rant about anything not going their way, and they would berate me for having the audacity to look up a little. Sometimes they would conspire to make even the positive things seem like negatives:

The treachery of absorption

When living away from home, and once you realise that the stay may be long term – things begin to change. You learn the language. You grow to love the food. You stop scanning the supermarket shelves for those things which you know you can’t get here anyway. In short, you learn to fit in. To do so can be quite gratifying – a successful experiment in cultural adaptation. This is not where you meant to be, and it may not have been your choice to come here – but you are making the best of it.

And then, the moment of treachery comes. You are walking through your new-found neighbourhood or talking in your new language with your new friends – when you stumble because you cannot remember the old ones. Perhaps you struggle for a word which was once so familiar on your lips and it just won’t come. You’re glad the people in that other country can’t see you now, because you would feel ashamed.

There are days now, in this land of grief – where I feel like I am starting to fit in. I recognise that single man in the mirror and do not flinch. I look at on old picture in a new space or sit in a new chair in an old room and it feels…normal. Then there are other moments where that new normal feels like a treachery to the old. It feels like the person who has studied their new language so hard that when a newspaper comes in their mother tongue, they can no longer read it. Absorption, which was such a laudable aim, feels like treachery in that moment.

To understand the bereaved person is to understand that this kind of internal conflict can go on for months, or even years, after the death. Bereavement is a deep wound with no visible scar.

If we are to make a change within this landscape of grief, then we shall all have to make adjustments, I think. Friends and family will have to embrace the joyful danger of getting it wrong for the greater good of getting it right. Employers will have to recognise that the incapacity brought about by grief may far outlast any bereavement leave they give. The bereaved themselves will have to speak a little more in the foreign tongue of this place to which they have moved. And we shall all have to recognise that the scars left by grief, like the patina on a much-loved antique – may add to our value rather than diminish it.

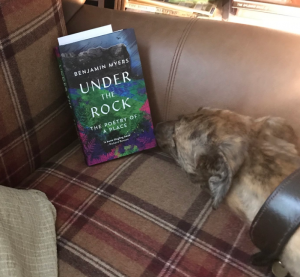

There’s a tree I often pass on my morning walks with the dog, and I want to leave you there this evening. At some point in its life the tree, on Greenham Common, has been all but uprooted. The main trunk now lies parallel to the ground. Springing up from it, though, is new growth – defiant and wonderful. I call it the Courage Tree – and I would like to see forests of them all across the country. Maybe with Sue Ryder’s help, we will.